Documentary Provides Insightful Look into the Art of Writing Obituaries

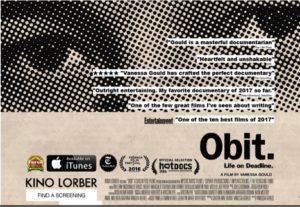

November 1, 2017Obits used to be dry, dull reports but not anymore. Today’s obituaries strive to educate and entertain readers. The job of an obituary writer is a quest to discover as much as possible about the life of the person he or she is covering – all in one day’s work. The documentary, Obit. Life on Deadline, directed by Vanessa Gould, takes viewers through a typical day in the life of the team of obituary writers at the New York Times.

“It’s counter intuitive, ironically, but obits have next to nothing to do with death and in fact absolutely everything to do with the life,” said Margalit Fox, Senior Writer.

Obit features former and current obituary writers such as Bruce Weber,  Margalit Fox, Paul Vitello, Jack Kadden, Daniel E. Slotnik, William Grimes, and the Obit Desk Editor, William McDonald, among others. We also meet Jeff Roth, the archivist at the New York Times, and Jon Pareles, Chief Pop Music Critic.

Margalit Fox, Paul Vitello, Jack Kadden, Daniel E. Slotnik, William Grimes, and the Obit Desk Editor, William McDonald, among others. We also meet Jeff Roth, the archivist at the New York Times, and Jon Pareles, Chief Pop Music Critic.

The film opens with a phone ringing. Then we see writer Bruce Weber on the phone asking questions about the life of William P. Wilson, the man who advised John F. Kennedy on his television and media appearances – and may have influenced the outcome of the 1960 presidential election following the televised debate between Kennedy and his rival, Richard M. Nixon. Scenes and interviews cut back to Weber throughout the film to chronicle his day of writing Wilson’s obit as he races against the clock – from the basic legwork of gathering information from relatives, public records and the archives, also called “the morgue,” to writing his article; gathering photos; meeting with the team; and getting the lead just right.

Obituary writers are first and foremost storytellers who weave together the life and accomplishments of newsworthy individuals who pass away – and they are able to maintain their sense of humor in the process. At one time, journalists who were being punished for some transgression would be assigned to the obituary department, but that has changed over the course of the last twenty years. Today, the obit writers at the New York Times find pleasure in bringing to light the life of their subjects. They worry about doing the person justice and getting all the facts right. In fact, Weber says he loses sleep over any mistakes he might make and feels terrible when he has to print a correction for someone’s obituary. However, Weber says family members sometimes remember things incorrectly. The writers are committed to reporting the facts, covering unsavory details such as jail time along with positive accomplishments, regardless of how loved ones remember the details.

But being an obit writer is a dying occupation. One writer says, “There aren’t too many of us doing this anymore. You can count them on one hand.” But the ones who are left are infusing a new vitality and humor into this form of journalism. Fox said that a grimness left-over from a Victorian sensibility used to dominate obituaries and dictated that they had to be somber, serious and devoid of humor. Today’s obituary writers celebrate many aspects of a person’s life, including the positive and the negative impacts, and they aren’t afraid to find the humor in our shared human experiences. Fox gives the example of the obituary of John Fairfax, the first low oarsman to traverse any ocean. She says his obit broke all the rules and was “just as rollicking and swaggering as the subject.”

Who Gets an Obituary?

At the beginning of the work day, the writers gather in an editorial meeting to decide who to write about. Weber jokes that he comes to work and asks, “Who died today?” He explains that an obituary must be written about a “newsworthy person” and says that “a good person is not newsworthy.” Weber says he gets ten to fifteen calls a day from relatives asking for an obituary about their loved one because he or she was a loyal New York Times reader, but that does not make them newsworthy. Other than the fact that the person died, all subjects must have lives that had an impact of one sort or another explains Weber – whether it’s an impact on the world stage, such as the death of Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev, or a cultural impact, such as the inventor of the slinky.

The reality of obit writers is that they have to put a word-length on a human being’s life. Most obituaries top out at 900 words, but the more prominent ones go from 1,000 words to 1,400 words. At 15,000 words, the obituary for Pope John Paul ran several pages and had a number of photographs. The number of words does not judge the worth of the life but the newsworthiness of the subject.

The 4:00 pm managing editors meeting determines who goes on the front page; above the fold is the best position and a blurb at the bottom of the front page as the second-best position. During the photo meeting, editors review photos onscreen to decide the best images to run along with the obituary.

The film gives us a glimpse into the Times “morgue” or archive, which consists of a warren of filing cabinets full of clippings. At one time, there were ten thousand drawers of clippings. But the clippings, along with the department, has shrunk in size. The morgue staff went from thirty people down to just one, Jeff Roth. Roth says it may look chaotic, but it is organized by people, subjects, and even by geographical locations. Writers and photo editors utilize the morgue to find information and images on their subjects.

Roth also explains that they keep advanced files on prominent people to be ready at the time of death. Roth says they have 1,700 advances, including people like Jane Fonda and Stephen Sondheim.

Weber says that his job does force him to think about death every day, but it also has the profound effect of making him think about mortality and what that means. He realizes that life does not go on forever, and he thinks about how best to spend the time he has left.

For Your Loved One

At Keohane Funeral Home, every life matters. “We help our families tell the life stories of their loved ones through personalized tributes and moving memorial services. We can even help them write the obituary for their loved one,” said Co-President, Dennis Keohane.

To speak to one of our knowledgeable funeral directors, please contact us at any of our locations or call our main office at 1-800-Keohane (800-536-4263).

Leave a Comment